Shelf Life by Betty Evans

By Elizabeth Evans

A joy of being 70 is that not only can one look forward with confidence to the mercies of God that are new every morning, but enjoy in retrospect the motifs of life that spring to remembrance from time to time.

A joy of being 70 is that not only can one look forward with confidence to the mercies of God that are new every morning, but enjoy in retrospect the motifs of life that spring to remembrance from time to time.

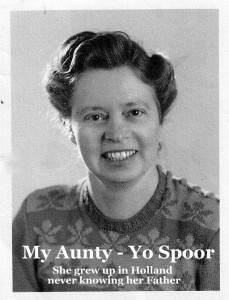

This vignette of Aunty Yo escaped from my past into things to consider.

My Grandfather, of humble status, was called into service for a wealthy aristocratic family in Holland to tutor their ailing daughter in English. The inevitable happened and the two young people fell in love and married in spite of considerable opposition from the young ladies family.

Following the marriage arrived Bob, Lena, Wijtske and Con.

My grandmother’s health continued to be fragile, and the medical advice was that there should be no more children. This advice was taken on board but there came a celebration when too much wine was enjoyed which resulted in the birth of another daughter, Yo, and the death of her mother.

The personal griefs, assumed blame, responsibility to his 5 Motherless children, the angst of the in-laws, were desperate days for my grandfather. Soon after, he married a farmer’s daughter, who my Mother remembered as a wonderful loving step- mother.

The Spoor family immigrated to Australia. The poignancy of the story is that Dirk Spoor was so pressured by his in-laws that he agreed to give Yo into their care in replacement for the only child that they had lost in childbirth.

The Spoor family immigrated to Australia. The poignancy of the story is that Dirk Spoor was so pressured by his in-laws that he agreed to give Yo into their care in replacement for the only child that they had lost in childbirth.

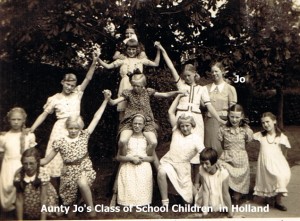

In Australia, the Spoor family increased, and endured the frugal times of the Australian outback pioneers, to finally have a stud farm of considerable fame in the Mundubbera area. Yo on the other hand was a child of privilege, to become a head mistress of an elite girl’s school in Holland. There was no contact with her birth family.

The pull of blood is strong and as an independent woman Yo made contact with her Australian family and came to visit.

This is where my personal memory begins.

My cousins have their own memories of this visit for by this time the adult siblings were scattered throughout south Queensland. Each of Yo’s brothers and sisters and step siblings shared their wonderful stories about the father they all admired and loved. Con and Wijtske (my Mother) were church workers in North Queensland. Aunty Yo visited us in Aloomba when I was about 11.

Wow! What a lady. I was in awe of her beautiful things. Every extra penny earned by my Dad went into God’s work. I don’t know who supported Uncle Con – probably Home Missions which explains the very simple living standard. In spite of our humble living Aunty Yo was one among us.

We took Aunty Yo on the kind of holiday that cost very little but gives what money cannot. We set up camp in the midst of the tropical forest on the Atherton tablelands. Words cannot describe the wonder of the canopy of majestic figs that tower above, the lawyer cane that drapes like paper streamers from tree to tree, the orchards and stag horns dripping from the massive tree trunks and the undergrowth of large and delicate ferns that form the carpet below. Added to this are the sounds of the forest-Amazing!

Amenities were simple- a bucket of water for washing, a few pieces of news paper and a walk to privacy behind dense foliage. One privilege afforded Aunty Yo was a jam tin instead of the night walk into the bush. I still remember the hilarity and my Aunts dismay in the morning to find that she had used someones boot instead of the jam tin!!

In the evening we children took Aunty Yo to explore the wonder of the phosphorous fungi growing on the root systems of the forest trees. I remember my Aunty’s absolute delight in the evenings when she was able to write up her diary by the flickering light of the fireflies we children had gathered and released under her mosquito net.

On the last evening my Mother and Uncle Con entertained us with stories of their childhood. The dominant feature of these stories was my grandfather and Yo’s father.The deep love and respect was evident- a wise, humorous, hardworking, inventive, loving, caring man.

I can still feel the pathos that followed. The hilarity was punctuated by a deep choking sob and deep deep crying as years and years of pain poured out from my Aunty. They told me he was a bad man she sobbed. Everywhere Ive been my siblings speak so lovingly of him I believed that I was the product of a bad man and a dead Mother.

At 11 years of age, even then, I knew the enormous sadness of loss that could never be regained. I thought of how Yo would have loved to have shared the stories of the very different and exciting family that was hers- even though separated by oceans. Growing up, did she feel unworthy in the false knowledge that her father was a bad man?  She had not married nor had children of her own.

She had not married nor had children of her own.

I never saw my Aunty Yo again. Shortly after her return to Holland she was diagnosed with breast cancer and soon after died. She was in her thirties.

As I write this tiny glimpse into Yo Spoors life, I cant but wonder how adult angst can steal so much from an innocent child. Each blood bond that is intrinsic within a child is a valued ingredient to the child’s personhood. Childhood has a shelf life, and when it is over its over. Those years cannot be regained.

Grandparents have a shorter shelf life. For that matter parents have a shelf life also. Yo’s people have all gone. Given a second chance would they have done it differently for the sake of a child?

Aunty Yo, do you have family in Holland who remembers you? I hope so. You have many nephews and nieces in Australia who wish we could have known you better.